Spielkarten

Playing cards inspired by traditional Central European and Pennsylvania Dutch design

Most of us are familiar with contemporary standard playing cards, ones organized with the so-called “French” suits (hearts, clubs, diamonds, and spades) in 52-card decks (A, 2-10, J, Q, K). But this is only one among many regional styles that emerged in Europe starting in the Late Middle Ages. Many of the earlier designs featured quite different suits, fewer cards (32 or 36 depending on the deck), and a broad palette of vivid hues.

Even today, you can find colorful German-style cards in southern Germany, Austria, and other parts of Central Europe. But folks from the English-speaking world can’t use them to play their favorite games because these decks have combined the ace and deuce cards, while the other numbered cards only go from 5 (sometimes 6) to 10.

I wanted to craft a deck that drew on this traditional design (as well as related folk art from my family’s traditions) while also providing the cards needed for the games I know best.

Standard deck of playing cards with German suits, Salzburger pattern (circa 1800) — Albert Field Collection of Playing Cards, Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University

About German-style playing cards

If you’re only familiar with modern playing cards, the suits here will likely strike you as strange. Sure, the hearts are mostly the same, and the leaves have a similar outline to spades. But instead of clubs and diamonds, we’ve got acorns and balls.

Unlike the English suit names, those in German are straightforward and plainly descriptive: Herz (heart), Laub (foliage), Eichel (acorn), and Schellen (jingle bell).

The face cards probably also seem peculiar. The king has no queen, and apparently, the jack has acquired a brother? These last two are called the Ober (“above”) and the Unter (“under”), sometimes depicted as men drawn from two different ranks (like knight and squire, or noble and burgher).

The artwork’s naive style and bold, primary palette are indicative of traditional Southern German design. Anabaptists from Switzerland and the Palatinate (in the modern German state of Baden-Württemberg) brought this aesthetic with them when they fled to the British North American colonies to escape religious persecution.

Today, we know them as the Amish and the Mennonites. Their distinctive folk art (called Fraktur) decorates barns and handicrafts throughout the Pennsylvania countryside, where my mother’s family has lived for over two centuries. Its influence on my illustrations should be apparent.

My reworked deck

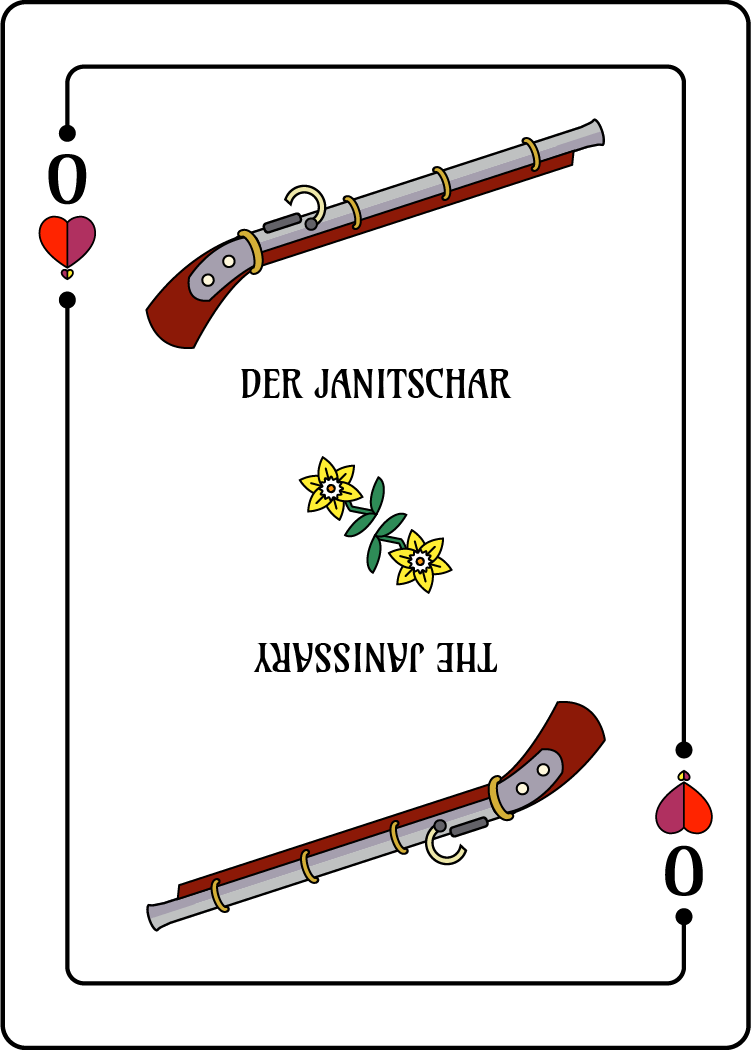

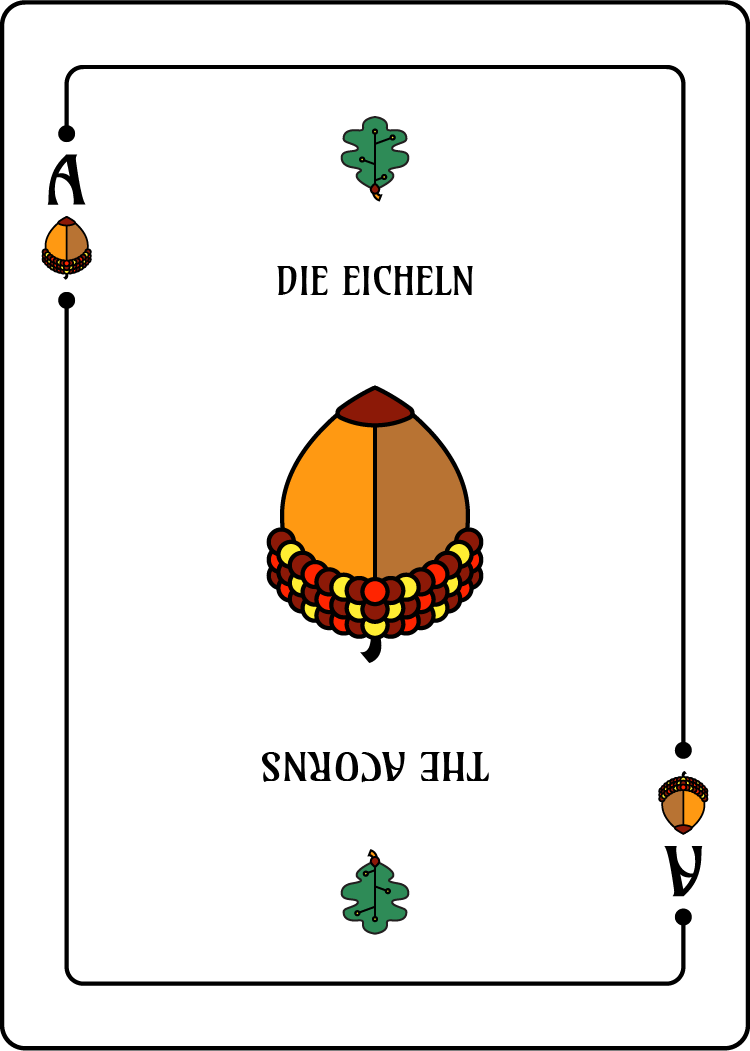

In my design, each König (king) is represented by the crown of a titled ruler, each Ober by the weapon of a warrior, and each Unter by a traditional artisan’s tool. I’ve created true aces, separate from the deuce cards, and added numbers 3 through 6 to yield a 52-card deck. And I’ve matched each suit with an ornament to capture some of the whimsical playfulness of the older designs.

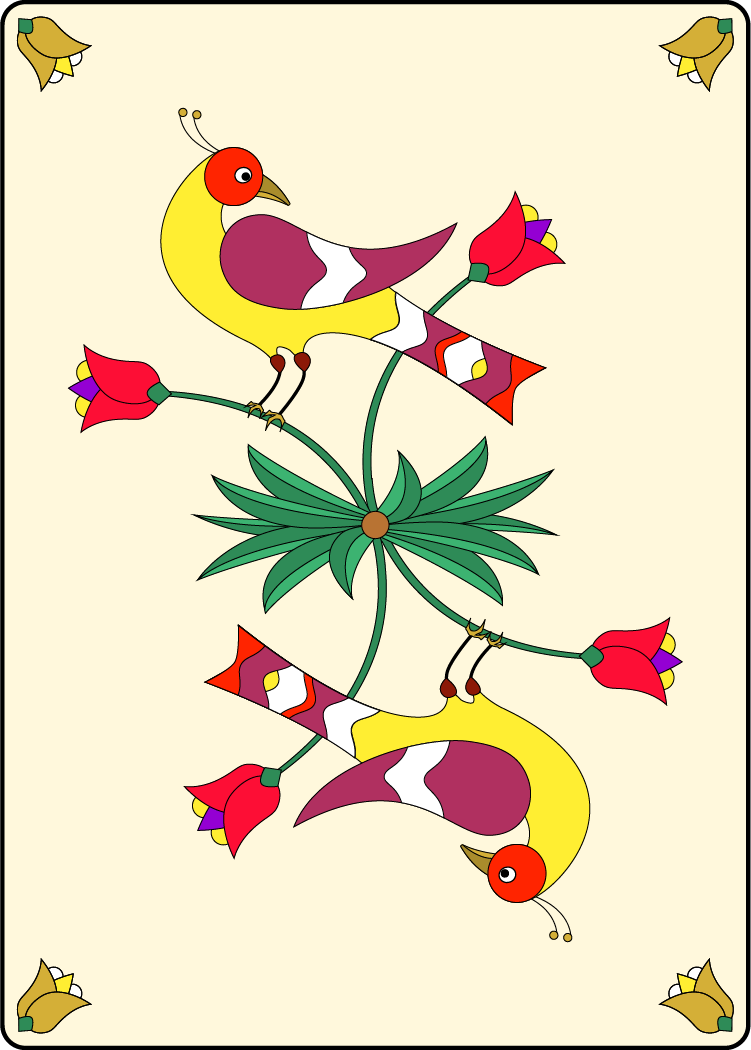

card back

Attribution

Herzen (Hearts)

Herzen have the same name and shape in both standard and German decks. I’ve just added a pendant heart to match the general form of the other suits.

ORNAMENT

A narcissus (daffodil), a favorite flower from my Oregonian childhood

KÖNIG

This card draws on the headgear of the Ottoman sultans. They didn’t wear crowns per se, but portraits often show them sporting this sort of jeweled turban.

OBER

Janissaries were elite Turkish soldiers who dominated warfare in the Balkans and Central Europe for centuries. We fancifully associate them with curved scimitars; in truth, they bore early firearms, giving them an edge over European armies still wielding more traditional weapons. (The Ottomans were also early adopters of the cannon, so I considered using some form of artillery instead for this card.)

UNTER

The heavy plow, fitted with a coulter and mould-board (to cut and turn the sod), was the essential farming tool until early modern times.

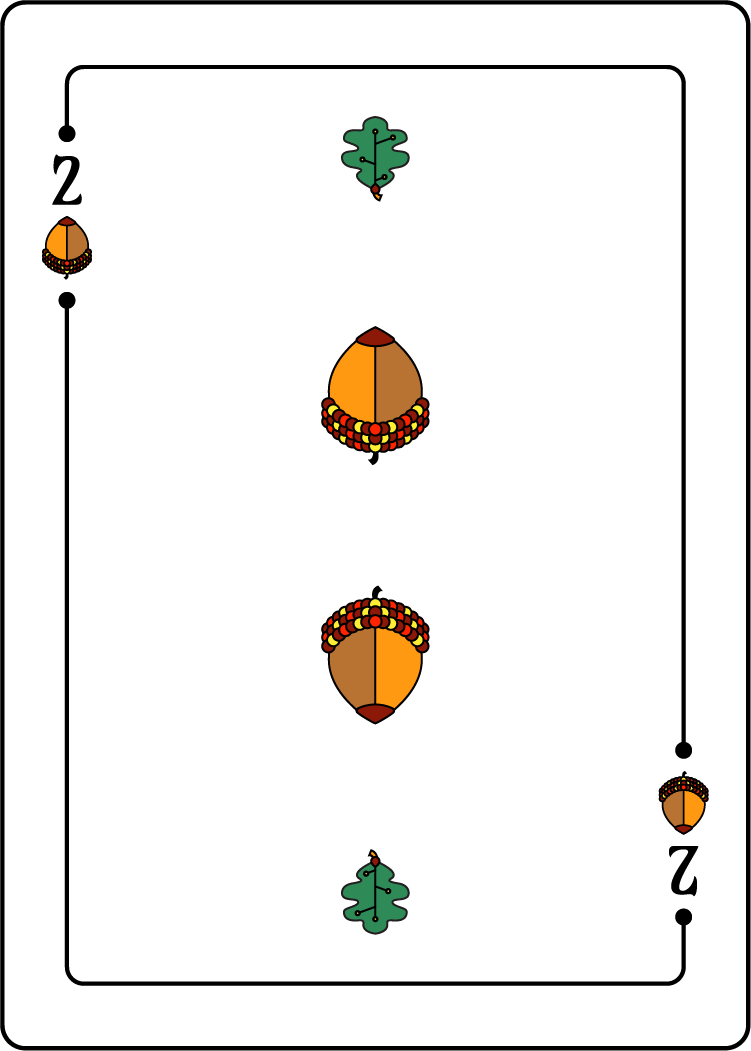

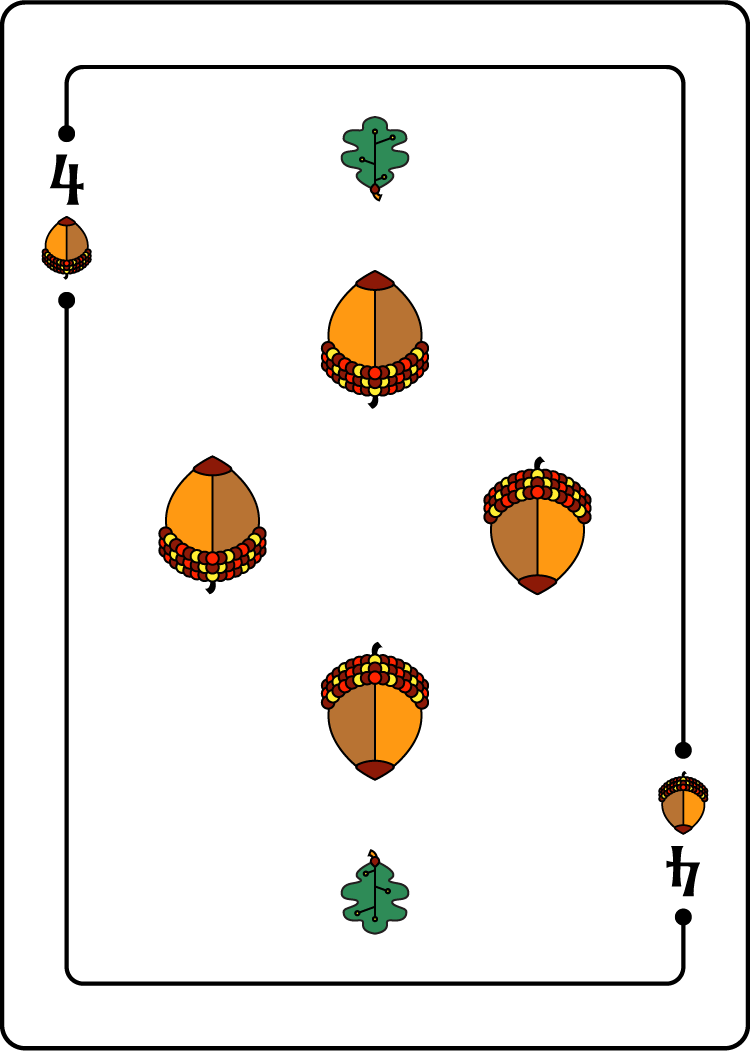

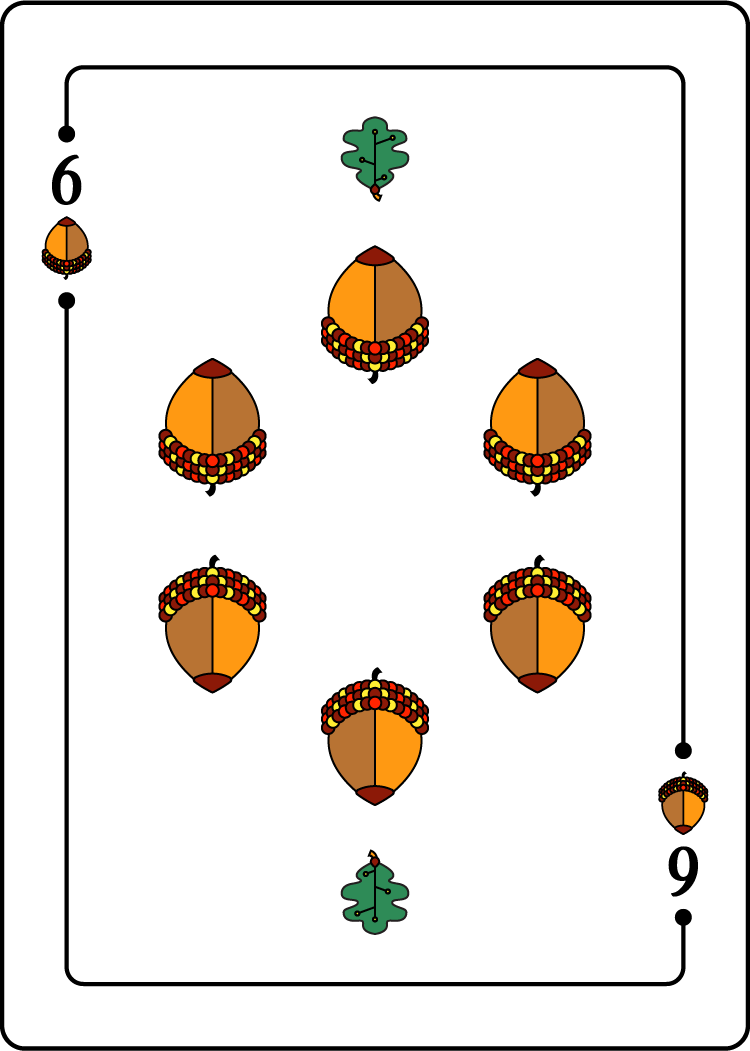

Eicheln (Acorns)

When playing cards entered Europe (via Italy), they had a suit represented by bastone (cudgel-like batons). “Clubs” is an English calque of this name, confusingly applied to the cloverleaves that the French used in place of the German acorns.

ORNAMENT

An oak leaf, naturally

KÖNIG

Here, the Imperial crown combines elements from different crowns worn by the Holy Roman (later Austrian) emperors.

OBER

Lances weren’t only for displays of toxic machismo at tournaments — these were hard-core weapons designed to skewer anyone in a rider’s path. And that “festive” bunting near the head? Its purpose was to soak up all the blood running down the shaft, so the spear wouldn’t slip from the wielder’s grasp.

UNTER

I’ve cheated and used a mid-19th Century design for the blacksmith’s anvil. Older styles were closer to simple blocks—effective, I’m sure, but lacking in visual appeal.

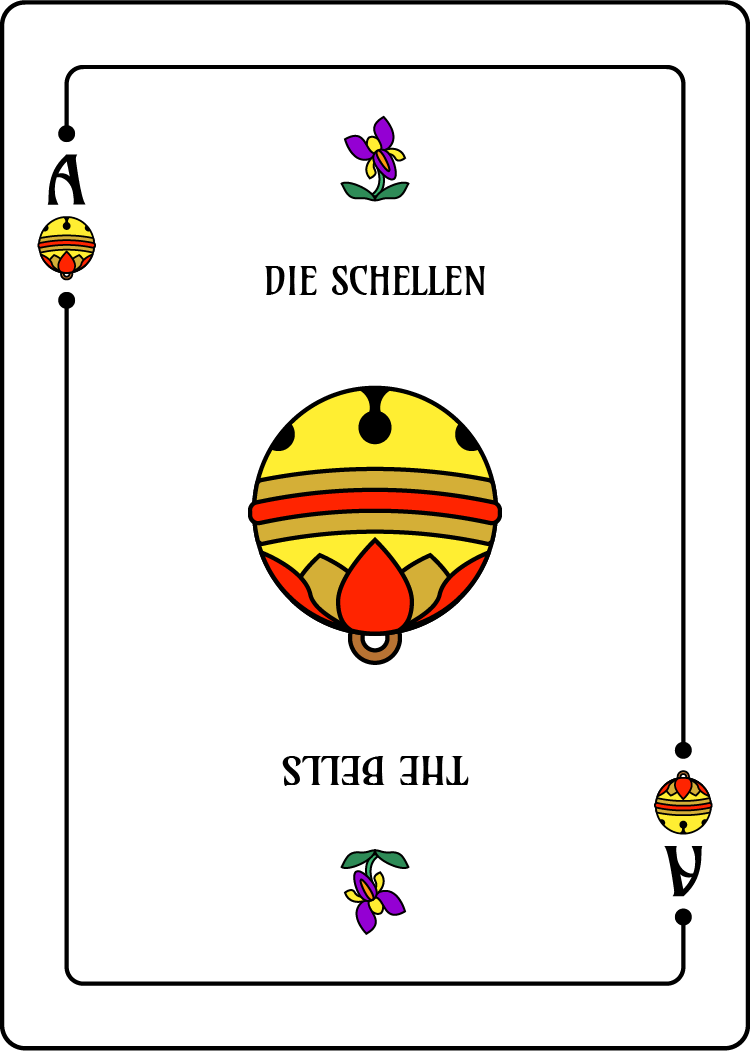

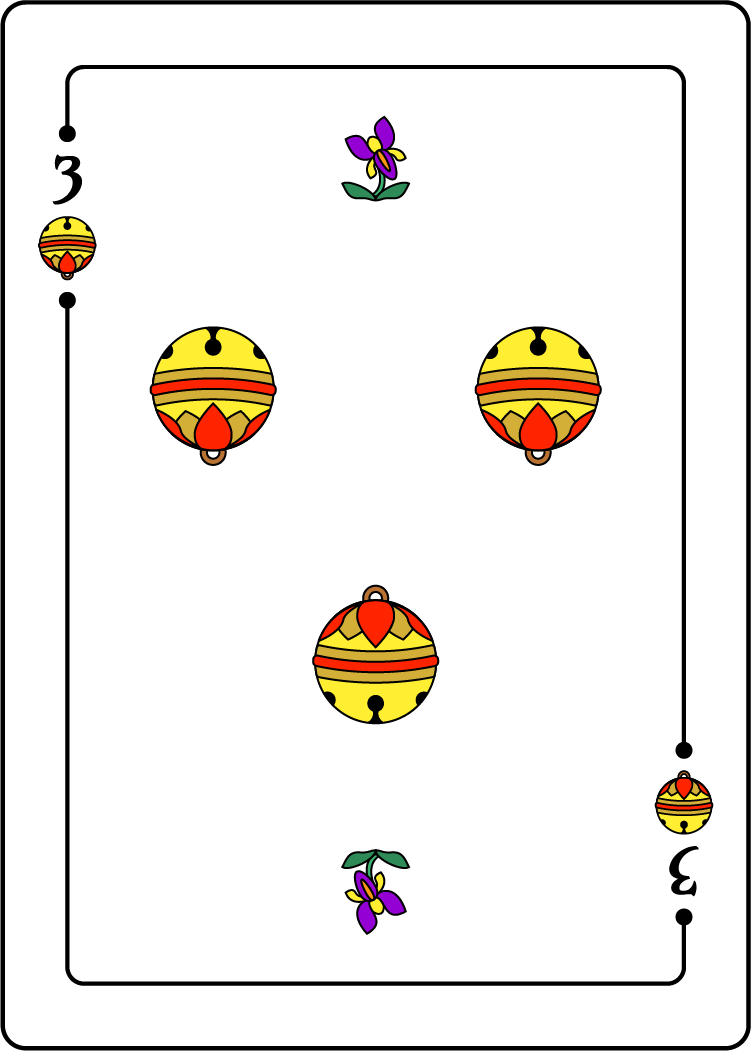

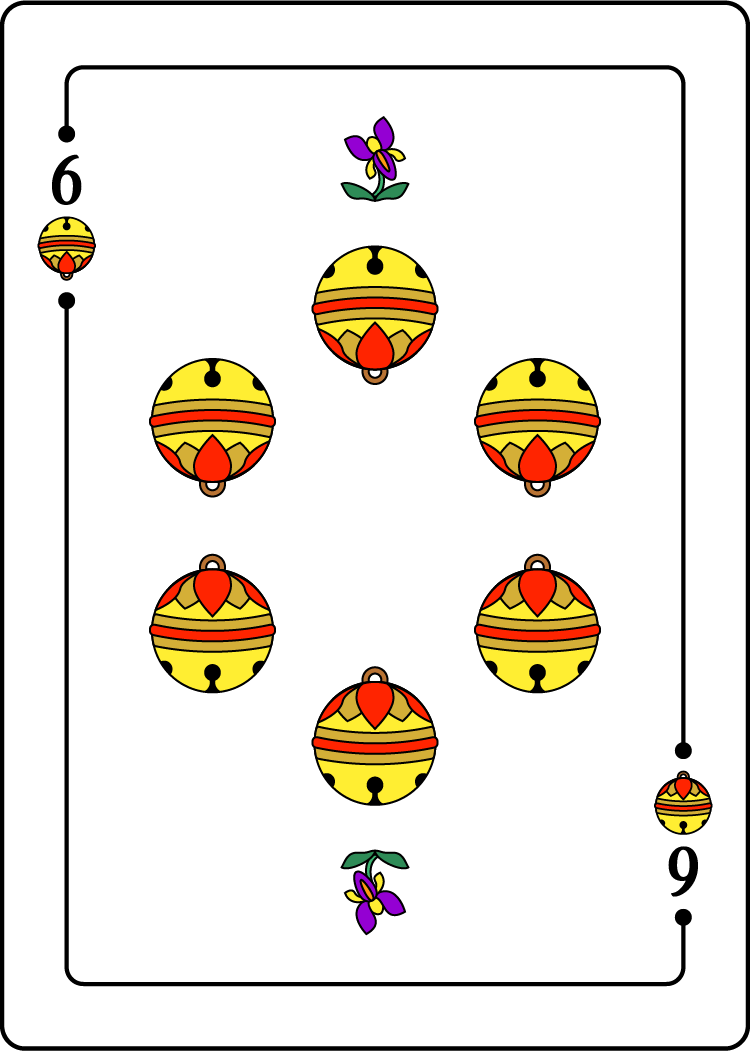

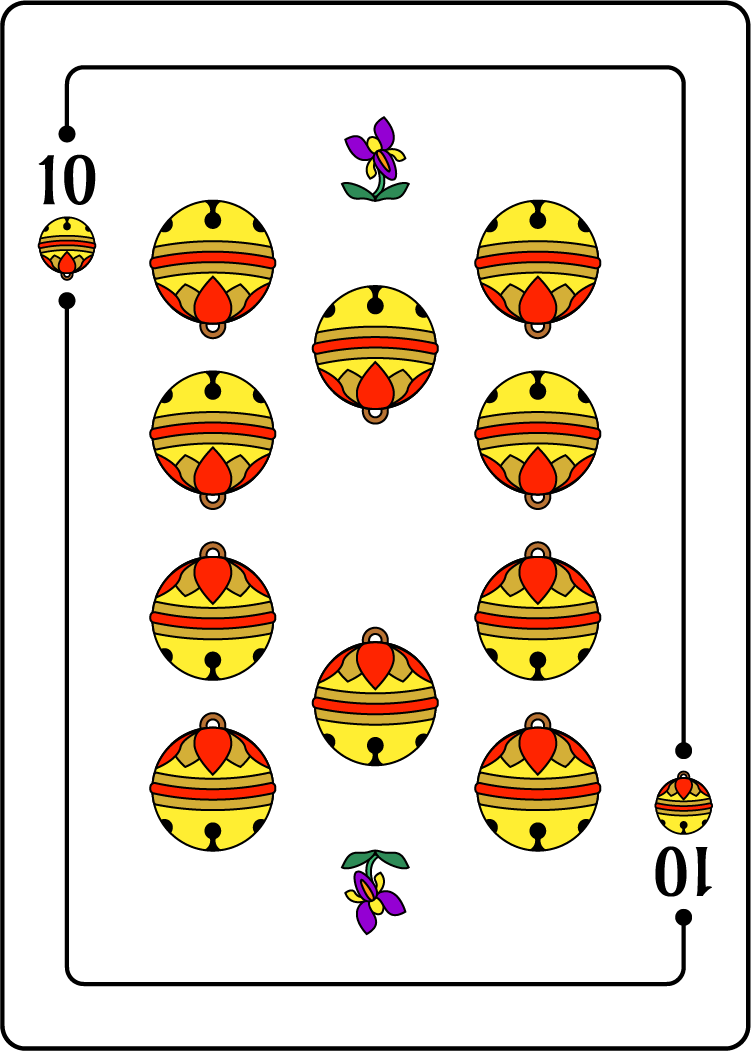

Schellen (Bells)

Fashioned from thin metal plates bent around a pebble, crotal bells have a long history. They often adorned horse harnesses as a warning to winter pedestrians unaware that a nearly silent sleigh was about to plow them down.

ORNAMENT

The iris always reminds me of my maternal grandfather, who was especially fond of a dwarf variety that grew in his extensive gardens.

KÖNIG

The Pope was once as much a temporal ruler as a spiritual leader; contemporary Vatican City is all that remains of the once-extensive Papal States that dominated much of central Italy. Today, the traditional papal tiara has given way to the less ostentatious preitosa, an embroidered miter with lappets.

OBER

The Swiss Guard has protected popes since the 16th Century. They’re easily recognized by their iconic halberds, the dual-purpose bêtes noires of mounted knights. Humble foot soldiers could pull a rider to the ground using the weapon’s distinctive hook and then dispatch him with its axeblade or spearpoint—a great equalizer in medieval warfare.

UNTER

The brace and bit is a refinement of the ancient auger, used by carpenters since the time of Christ and his wood-working dad to drill holes in beams and planks.

Laub (Foliage/Leaves)

asfafsda

Fraktur and the distelfink

Back of the cards

This is the bird

Fraktur and the distelfink

The Distelfinkis the Pennsylvania Dutch word for a golden finch, or “thistle finch,” which feeds upon the seed of the thistle and makes nests with the down. Since the golden finch curbs the propagation of thistle, farmers have admired the bird and considered it to be good luck, and a symbol of perseverance in the face of adversity. This inspired silkscreen artist Jacob Zook to mass produce a stylized Distlefinkas a hex sign in the 1950s, and it is still widely available at tourist destinations in Lancaster County today. Courtesy of Patrick J. Donmoyer.